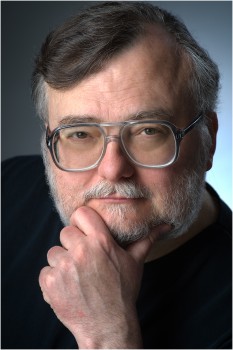

In the past decade, Stephen

Stirling has distinguished himself as one of the best and most innovative authors of alternate history. His work tends to be politically mature and historically well founded, with just enough wry humor and homage to Golden Age science-fiction authors to engage the reader in a way that is rare in today's genre fiction, making his books even more valuable.

Several years ago, Mr. Stirling was kind enough to give me an interview for my blog, which was later published (in translated form) in the Emitor fanzine. I've asked Mr. Stirling for another interview, which you'll be able to read in Serbian in a few weeks on this blog and come September in Emitor.

Enjoy.

NF: Before we start, I'd like to thank you for this interview.

I know you're busy and that you have a lot on your plate.

-- oh, any

displacement activity is welcome sometimes.

When we did our first interview, I asked you about which

writers influenced you as an author and what is your favorite book. Almost four

years have passed since then and we’ve witnessed a huge increase in alternate

history novels, with strong accent on steampunk. Do you follow the development

of the genre? Do you think that the alternate history has evolved since 2010

and in what way if so? Are there any new authors that you like and recommend to

your readers?

When we did our first interview, I asked you about which

writers influenced you as an author and what is your favorite book. Almost four

years have passed since then and we’ve witnessed a huge increase in alternate

history novels, with strong accent on steampunk. Do you follow the development

of the genre? Do you think that the alternate history has evolved since 2010

and in what way if so? Are there any new authors that you like and recommend to

your readers?

-- I’m always discovering new

authors. Django Wexler, for example, and

C.J. Carella, and Alyx Dellamonica, just recently. But I can’t keep up with the whole field the way

I used to. There’s just too much, and

also of course writing books leaves you less time for reading. In particular, for reading nonfiction.

NF: To follow up on that question, steampunk is becoming a big

deal. Some of your work has certain similarities in tone and setting to

steampunk norms. Do you have any plans to explore that subgenre? While we’re at

it, do you consider steampunk to be a subgenre of alternate history (a subgenre

of a subgenre) or its own thing entirely?

-- We all know

what we mean when we point to it; it can be alternate history, but it isn’t

necessarily. It’s a subcategory of the

argument about what constitutes SF, which was going strong when I was a neofan. I can say with pride (pointing to THE

PESHAWAR LANCERS) that I was doing steampunk before ‘steampunk was cool’. I’d be glad to do more in that vein, but

it’s futile to chase the “hot” genre; something else is hot by the time you’ve

got something, given the lead times in publishing.

-- We all know

what we mean when we point to it; it can be alternate history, but it isn’t

necessarily. It’s a subcategory of the

argument about what constitutes SF, which was going strong when I was a neofan. I can say with pride (pointing to THE

PESHAWAR LANCERS) that I was doing steampunk before ‘steampunk was cool’. I’d be glad to do more in that vein, but

it’s futile to chase the “hot” genre; something else is hot by the time you’ve

got something, given the lead times in publishing.

NF: Can you tell me, and my readers, how does your creative

process work? What sets you off, what is your inspiration? What prompted you to

write Dies the Fire or Draka novels?

-- something will

spark an idea; usually bits and pieces (a face, a scene) will come to me, and

then I start making up stuff around it.

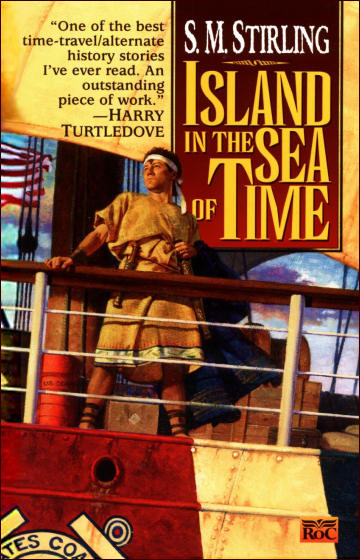

I was walking on the beach on Nantucket watching a ship’s light go by

when I came up with the idea for ISLAND IN THE SEA OF TIME; and even then I had

a vague idea of the flip-side DIES THE FIRE series in the back of my head. And a scene with Juniper Mackenzie came to me

when I thought about that.

But inspiration

is easy and talent is cheap; that’s why there are millions of people with

half-finished novels in a drawer. I

think it was Baudelaire who said that “Every little bourgeois feels inspired

when he sees a sunset. It’s application

that makes an artist.”

NF: When you write, do you work in a linear manner, or do you

jump back and forth between chapters?

-- generally

linear, but not invariably. Sometimes

I’ll write a scene as it comes to me, or do a sub-thread of the plot that’s

going to be woven in eventually.

However, linear saves time and effort in the long run for the most

part.

What about the sequence of novels in a series? Some authors,

such as George Martin or Patrick Rothfuss tend to write whole chapters of book

3 in a series, for instance, while still writing book 2. What is your approach?

What about the sequence of novels in a series? Some authors,

such as George Martin or Patrick Rothfuss tend to write whole chapters of book

3 in a series, for instance, while still writing book 2. What is your approach?

-- Nope, I

generally finish a book before starting the next one. The main exception is when a plot arc turns

out to take more space than one book can handle; then I split, which involves

some reworking because you don’t want to leave things hanging in air more than

you have to.

NF: Do you always work on only one project at a time, or do

you have two or more projects that you work on simultaneously?

-- sometimes on

more than one. I’ve found that working

on two solo novels at the same time is slower than writing one at a time, but

collaborations or editing an anthology or short fiction are another matter.

NF: How do you manage to stay focused while writing a huge

series of novels, such as The Change?

-- I write the books I’d like to read; always have, apart from

a few novelizations of movies (the Terminator books) and so forth.

What I do is make

sure that a series has a canvas in which I can write lots of stories that

interest me. I sometimes call the

Change/Emberverse books “my Hyborian Age”. Howard just crammed every potentially

interesting historical period into his antediluvian setting, so he could have

Cossacks fighting ancient Egyptians or an ancient Celt on the Spanish

Main.

I’ve got a

postapocalyptic Earth without high-energy technology, with regressed cultures –

though often they’re not as close to recreating the past as they think they

are. As a character (Japanese, as it

happens) says in THE GOLDEN PRINCESS (coming out Sept. 2014), “History cannot

be completely undone, even by the Change.

Nor can you truly bring back the past, even if you wear its clothes.”

I’ve got a

postapocalyptic Earth without high-energy technology, with regressed cultures –

though often they’re not as close to recreating the past as they think they

are. As a character (Japanese, as it

happens) says in THE GOLDEN PRINCESS (coming out Sept. 2014), “History cannot

be completely undone, even by the Change.

Nor can you truly bring back the past, even if you wear its clothes.”

If a fictional

world is substantial enough, it should have the same capacity for ‘story carrying’

that the real one does, and nobody’s run out of things to write mimetic fiction

about. It helps that the Change universe

is ours, with some modifications (glyph of understatement). That makes it easier to avoid the lurking

“sameness” of feel that a purely secondary world can have if you’re not

careful.

Do you approach this task as something you do for fun, or is

it a job for you?

-- I can’t not

write. I wrote my first book while at

law school – now there was a waste of time (the law school, not the

book). I also got fired or quit every

other job I ever had. This is my hobby

that I make a living at. If it weren’t

fun, I’d have stayed in law instead of taking crazy risks with my life.

Can you tell us about your day – when do you start writing,

how long do you write? Does this job leave any time for you to explore other

things than writing?

-- writers

usually lead rather uneventful lives(*), and I’m no exception. When I’m not travelling I have a pretty stable

routine. I get up around 10:00 am, do

the usual morning things, check my email, go to a local diner and have lunch

and start working. At 2:00 my wife and I

go to the gym, where we work out until around 5:30, counting changing time and

so forth. Then we usually go to a coffee

house where I work until around 8 or 9 (with a light dinner along the way),

then back home and work until around 2:00.

There are some variations in the times, and sometimes we’ll decide to go

for Chinese or some social engagement will intervene – on Saturday I went to

the premier and launch party HBO and George put on for the next season of Game

of Thrones, for example. Monday is our

holiday; we don’t go to the gym on that day and often take in a movie.

(*) Hemingway

said of his days on the Left Bank in Paris that you could tell the phonies from

the actual writers by the time they started drinking and talking. The real writers actually wrote first.

NF: You’ve grown in popularity over the last few years. You

are very much active on Facebook and you talk with your fans about different

aspects of your work. Also, from my personal experience I know that you reply

to fan’s emails. How do you manage to find the time for all of that?

-- well, I am

a fan; that and the writing/publishing world are the social milieu in which

I’ve moved since the 1980’s, and my friends tend to be fans or other

writers. In a sense it’s like being a

copyh; you have to have people who understand where you’re coming from. A certain degree of it is relaxing, and my

fans have been invaluable with things like research. My contacts within the pagan community have

been extremely important in shaping the Change series, for instance.

NF: For a long time, you have been considered a Crown Prince

of alternate history, with Harry Turtledove as the reigning King. Have you ever

been in contact with Mr. Turtledove, or any other alternate history author? Do

you talk about your ideas with your colleagues?

-- Oh, Harry and

I are old friends, and have been for… must be twenty years now and have

Tuckerized each other. He and I have

collaborated on some projects, and he has a story in THE CHANGE, an anthology set in the Change universe I’m

working on. We (and our other friends in

the field) certainly discuss ideas, but you have to watch that. Talking about a plot can de-energize you if

you’re not careful.

-- Oh, Harry and

I are old friends, and have been for… must be twenty years now and have

Tuckerized each other. He and I have

collaborated on some projects, and he has a story in THE CHANGE, an anthology set in the Change universe I’m

working on. We (and our other friends in

the field) certainly discuss ideas, but you have to watch that. Talking about a plot can de-energize you if

you’re not careful.

NF: Last year was

pretty important for your work. You’ve finished a second series of Emberverse

novels and Shadowspawn trilogy – is it a trilogy? Do you plan more work in that

universe? Also, you returned to your Lords of Creation universe with a story

published in the Old Mars anthology. Is it hard for an author to work on three

so very different projects in a relatively short time?

-- The Shadowspawn

books are a trilogy, and are wrapped up.

The Old Mars anthology was done for, basically, fun. In fact the Lords of Creation books (THE SKY

PEOPLE and IN THE COURTS OF THE CRIMSON KINGS) were a bit of a labor of love; I

took a hit and switched publishers for those, simply because I wanted badly to

write them as my homage to the pulps.

Conceivably I may return to the setting sometime, either for short

fiction or otherwise. These days the

possibilities are greater – I’m looking into e-publishing short fiction,

novella-length things. Until recently,

there was just no way to sell that length, which I consider a natural one for

many types of SF.

-- The Shadowspawn

books are a trilogy, and are wrapped up.

The Old Mars anthology was done for, basically, fun. In fact the Lords of Creation books (THE SKY

PEOPLE and IN THE COURTS OF THE CRIMSON KINGS) were a bit of a labor of love; I

took a hit and switched publishers for those, simply because I wanted badly to

write them as my homage to the pulps.

Conceivably I may return to the setting sometime, either for short

fiction or otherwise. These days the

possibilities are greater – I’m looking into e-publishing short fiction,

novella-length things. Until recently,

there was just no way to sell that length, which I consider a natural one for

many types of SF.

NF: I enjoyed the Sword of Zar-Tu-Kan very much. What are the

chances for the next novel in Lords of Creation series? You’ve stated that you originally planed

to do a trilogy set in that universe, with third book being an homage to

Pelucidar. Is that still true? What about more Mars stories?

-- right now

publishing considerations make a third LoC novel unlikely. Short fiction is more probable.

NF: Last September the final novel in the second Emberverse

series was published, The Given Sacrifice. I’ve enjoyed the hell out of it, although

I’ve struggled a bit with a fact that I – and everyone else – knew how it ends

even before I started reading it. There were some mixed reviews on the

Goodreads and there are readers who think that the ending of the novel was anticlimactic.

I’ve compared it to the ending of the Lord of the Rings, when Hobbits return to

the Shire. Anyway, we all knew what will happen and that predetermined course

of events was for me something that encouraged me to read the series, all the

while expecting that bittersweet moment when it all ends. Now, I presume that

this was not an easy book for you to write. Can you tell us what were your

thoughts before you started writing The Given Sacrifice? Did you have to

struggle with certain parts, did you plan everything in advance or did the book

grow organically?

-- well,

obviously I knew Rudi was going to die young.

That was part of his story arc from the beginning. He was a bit of an experiment; I wanted to do

a Real Hero™. Not an ironic

deconstruction of the mythic hero – that’s become a bloody cliché and done to

death. What I wanted was a true Fated

Hero King, the king who dies for the people, someone like Sigurd or Beowulf

whose life plays out in mythic time, but done with Modernist technique. It was interesting.

The hard part of

LORD OF MOUNTAINS and THE GIVEN SACRIFICE was structural. The arc of the Prophet’s War turned out to be

too long for one book; and the early years of his daughter Órlaith’s life was

too short, so I split one and led into another, uniting them with the fated

hero’s death.

The hard part of

LORD OF MOUNTAINS and THE GIVEN SACRIFICE was structural. The arc of the Prophet’s War turned out to be

too long for one book; and the early years of his daughter Órlaith’s life was

too short, so I split one and led into another, uniting them with the fated

hero’s death.

Incidentally, one

of the things I don’t like is fantasy/SF where the decisive battle ends the

struggle. That’s not the way big

conflicts actually happen. If you look

at WWII, for instance, the issue of who was going to win was settled in

1941-42. But the bulk of the fighting,

killing and dying happened after that.

Human beings don’t just give up because their position is hopeless…

though the Martians in IN THE COURTS OF THE CRIMSON KINGS very well might. So I didn’t want to end the Prophet’s War

business with the Battle of the Horse Heaven Hills, though that was the natural

denouement for the book. It made a

logical place to split them. When you’re

dealing with a series, where one “book” ends and another beings is always to a

certain degree arbitrary, a product of the business model of publishing and the

demands of paper-and-ink distribution.

Notoriously so for Tolkien, who wrote all three books of the LOTR as

one.

NF: There are lots of deaths in this series – some of them pretty

grim. How do you decide which character to kill? Do you think about which death

will have the greatest impact on the readers, or do you come by the decision in

the moment, impulsively?

-- Well, none of

the human characters are physically immortal!

Usually it’s a matter of what feels “right”. It’s hard to describe that sort of thing; you

try various scenarios in your head and they seem more or less harmonious with

the structure you’ve established. And of

course, if you’ve got lots of people in dangerous situations and trades, some

of them are going to die. Gustavus

Adolphus died of a stray shot riding into a fog, for example.

NF: I’ve seen some comments that your work tends to be

influenced by current politics. Some consider you to be a right-wing author,

while others think of you as a liberal one. From a European standpoint, you

come across as a Centrist, with perhaps slight tendencies to the right side of

political spectrum. Perhaps none of this is true, but do you feel that your

writing is influenced by your personal political or philosophical principles?

-- One of the early

Hollywood moguls, I think Samuel Goldwyn, said “If you’ve got a message, use

Western Union.” Or these days, a blog

post or a tweet. My politics don’t

really fit on the American spectrum, since I was raised outside the US – I’m a

monarchist by inclination, for example, and my favorite 19th-century

politician is Lord Salisbury. In any

case, they’re not really relevant to what I write, since most of the settings I

use are ones where the issues of a modern Western society simply don’t arise.

I consider it

sloppy worldbuilding for people to be culturally/psychologically modern

Westerners in a setting where the economic, cultural, social and historical

settings make that unlikely. Granted,

showing people who are really different makes the author’s task more difficult

since it’s harder to get reader identification, but one should try. Otherwise you might as well have them

tweeting as they storm the castle or invoke the Great God Ghu. It’s more interesting to deal with people for

whom issues like, say, dynastic legitimacy or good lordship are desperately

important, or ones who live in a mental universe full of numinous supernatural

presences.

That being said,

your general worldview – how you think human beings and reality in general

operates – cannot but inform your writing.

NF: Can you tell us something more about the Golden Princess?

How many novels are planed in this series, or is that yet to be determined?

-- THE GOLDEN PRINCESS

is the first in a new arc. Obviously, it

takes up immediately after the ending of THE GIVEN SACRIFICE; on the next day,

in fact. But the canvas is different;

instead of being largely limited to North America, the whole Pacific Basin will

be involved, the whole sweep from Australia to Korea. Hence the Japanese characters introduced at

the end of SACRIFICE, some of whom will be central to the plot.

As of now there

are four books planned; THE GOLDEN

PRINCESS, THE DESERT AND THE BLADE, PRINCE JOHN, and THE SEA PEOPLES.

NF: You started accepting stories for the Emberverse

anthology. Can you tell us a bit more about the concept of that book? Do you

plan to include some established authors?

-- I gave the authors

pretty well free reign, except that there are no big violations of the canon

I’ve established. Contributors include

Harry Turtledove, Alyx Delmonica, John Barnes, Diana Paxson, John Birmingham, Kier

Salmon, John J. Miller, Emily Mah, Matt (M.T.) Reiten, Jane Lindskold, Lauren

C. Teffeau, Walter John Williams, Victor Milan, Terry D. England and Jody Lynn

Nye. I’ll be doing a story for it

too. There may be another volume, though

that depends. I think it’s a nice

balance of established, new and completely new authors. Entirely by coincidence, it also has an

almost exact balance of the genders, which I didn’t notice until last week.

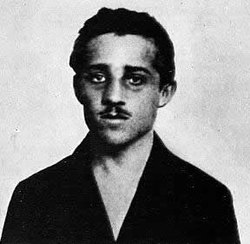

NF: You talked about writing a Gavrilo Princip story. What are

your thoughts about him as a historical figure? Do you consider him a terrorist

or freedom fighter? Have you ever visited former Yugoslavia?

-- I’ve never been to

that part of Europe, though I’d like to someday. I think Princip was a sincere, idealistic

dupe, which is the type who cause much of the world’s problems; his main

personal fault was a raging sense of personal inadequacy. The guy behind him, Dragutin Dimitrijević (aka

Apis, head of the Black Hand), was much smarter, definitely a terrorist, a

moral imbecile, and an example of self-pitying narcissistic nationalist

sacroegoismo run amok. I’ve got nothing against nationalism as such, being a

nationalist myself, and conflict is part of life, but you have to retain a

sense of proportion or catastrophe can all too easily result. WWI was, of course, an unqualified disaster

whose consequences we’re still suffering.

The fall of the Dual Monarchy was one of them, though not the worst by

any means. The whole concept of the

nation-state was only workable in that part of the world after a lot of human

engineering – aka “mass killing”. It

used to be said that a chameleon put down on a color-coded ethnographic map of

the Balkans would explode, but that’s no longer true… if you don’t count the

dead.

NF: To conclude – what do you think you’ll be writing in five

years? Where do you think that publishing is going? Is traditional model still

viable? Do you think that the e-book boom is over, or do you foresee an

increase in e-book sales?

-- Well, I’m already

contracted for books that will run to 2018, so I more or less know what I’ll be

writing. Ebook sales will undoubtedly

continue to increase, though not forever at the current rate; nothing ever

maintains that steep an upward curve over the long run(*). It’s impossible to predict how publishing

will go, though I feel fairly sure readers will continue to pay for

fiction. Self-publishing has become more

viable, of course, though people tend to forget what publishers actually do.

Production and distribution of dead-tree books is the least of it; only about

15% of total costs go to that. The

editorial function, and promotion, are the rest. Anyone who’s read the tidal wave of utter

tripe that pours into publishing houses, tens of thousands to each every year,

knows that wading through it yourself would be agonizing. When you pay for a book you’re paying for

that filtering service, and believe me it’s cheap at the price.

The most notable

single result of the rise of the ebook is that nothing goes out of print any

more. It used to be that most popular

fiction was only on the stands for weeks or at most months, after which it

became hard to find. That no longer

happens. The most immediate result from

an author’s point of view is that royalties have returned as a major source of

income. Ten years ago royalties were a

very minor part of my (much smaller) income; I’d take my wife out to dinner

when we got a check, or buy an expensive hardcover. Now they’re about a quarter of what I earn,

or even more. Ebooks also make impulse

buying much easier. People read one

book, like it, and then go and buy the entire series, or even everything the

author has written. Needless to say, I

approve!

(*) including

specific technologies, which tend to follow an S-curve. Science Fiction almost always gets this wrong

by assuming that the upward curve will continue indefinitely. For example, if the curve of maximum speeds

between 1903 and 1963 had continued, we’d have interstellar travel by now and

possibly FTL. Instead the first jet

aircraft I flew on, as a child of 11 in the 1960’s, travelled at almost exactly

the same speed as the one I flew across the Atlantic on to go to World Fantasy

in Brighton last year. Given the

ubiquity of the pattern, I have absolutely no doubt that current

rapidly-advancing technologies will follow the same S-curve.

Thank you for your time.